In the U.S. Healthcare System We Are Customers, Not Patients

By Ella Lee / Spring 2021

In the last 12 years of my immigrant life, I visited my home country, Korea, about five times. I went there for multiple reasons: to see my family members, to buy things I needed, but most importantly, to go to the hospitals. There are more than 6,000 hospitals and more than 1 million practicing physicians in the United States... but why do I fly back to Korea, at the expense of over $1,300, and of a 25-hour round trip? It’s because it is easier. Not only that, it is cheaper and faster. As soon as I land at Incheon International Airport, I can visit almost any specialist hospital, public or private, and wherever I choose to go, the National Health Insurance Service will cover most of the costs. In Korea, no hesitations or financial barriers stop me from taking care of my health.

My experience of visiting doctors in the U.S. was completely different. Four years ago, when it hadn't been too long since I first moved to San Diego, I started feeling pain in my right ankle. I endured the pain for several months, because I didn’t have insurance at that time. Also, I knew it would take days and weeks to finally see an orthopedic specialist. I have also heard from and seen people who got bombarded with expensive medical bills after their visits to doctors. The complicated process, anticipation of waiting, and the unpredictable amount of medical bills kept me from visiting the doctors here in the United States. I was only able to get my ankle checked after I transferred to UCSD in 2019 and was enrolled in UC SHIP. The short 5 minute conversation with the doctor and an X-ray cost me over $1,000. It is hard to even imagine what I would have done without the insurance.

Here is another story I came across on an online forum. It was written by the mother of a sixth-grade boy who fell down the stairs at school and got his chin torn. She took her son to the emergency room and got his wound sewed up. The reason she wrote on the forum was because of the bill she got a month after her son’s visit to the ER, which was over $10,000. The mother wrote that she called the hospital and told them about her insurance, but they replied the price has already been adjusted according to her insurance plan. Shocked by the exorbitant, unaffordable amount, she was desperate for advice from other people on how to deal with the situation. This story may not be very surprising, but rather relatable to many Americans who have been in a medical emergency situation. In fact, approximately 65% of bankruptcies in America are caused by medical related issues. When people first come to see how complicated and expensive American healthcare system is, they often ask, “What do we do if we get sick? ” I did so too. Most of the time, we reach this simple but bitter conclusion: “Just don’t get sick.” I used to think it is what it is. It was the Pay or Die game, in which the wealthy survive and the poors lose. This is the logic, the rule of our capitalist society, isn’t it? But, if we take a closer look at it, we realize it is not a fair, democratic game that we are playing.

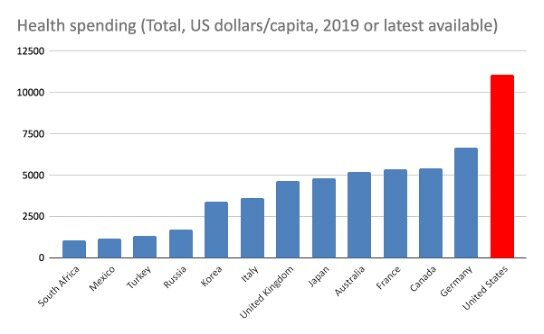

As I dived deeper into this topic, I came to wonder what really makes the healthcare service so expensive. I see people giving me a simple answer to this, “Because we spend more on healthcare, it obviously costs more.” Well, then why do we spend so much more than other countries? Again, Google shows us hundreds of articles saying “It’s because Americans receives more medical care than other countries,” or “It’s because of malpractice insurance,” or even “It’s because we’re obese!” Yes, it is true that the U.S. has higher rates of obesity compared to other countries. But even considering that, we pay way more than any other OECD countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Health spending. Total / Government / compulsory / Voluntary, US dollars/capita, 2019 or latest available (data.oecd.org)

And actually, Americans don’t even visit doctors that much — The U.S. is not even on the top 30 list (Figure 2). These reasons we find on the internet tries to convince us that the prices are reasonable and fair. Not only that, they say it is our fault going to the doctors too often, or becoming obese. This leads us to think again that “it is what it is.” But now I want to tell you, that whenever they say “everything is fine” or “there is nothing we can do about it,” it is a sign that something went wrong, and that we must take action. Before I discuss further on this topic, I want to tell you a little about the history of the U.S. healthcare system — where and when everything started.

Figure 2.

Doctors’ consultations (among 37 OECD countries) Total, Per capita, 2019 or latest available. (data.oecd.org)

The archetype for today’s insurance plans comes from the early 1900s, when Baylor University Hospital introduced a deal to the local teacher’s union. Those signed up for the contract could receive up to 21 days of inpatient care a year for 50 cents a month, or $6 a year which is approximately $100 in 2021 dollars. This model soon spread across the country and led to the development of Blue Cross Plans, which was a tax-exempt, not-for-profit insurance plan based at the state level. These providers accepted everyone regardless of their health or financial status. During the 1950s, with the advancements in medical technology, the price of hospital care doubled. The number of Americans with health insurance exponentially increased and such demands created, America’s all-time favorite, a business opportunity. This led to the emergence of many commercial, for-profit insurance companies that only accepted younger, healthier individuals on whom they could make a profit. Meanwhile, the first for-profit hospitals started to appear around the country, and by 1982, about 1 in 7 hospitals in the U.S. were either owned or managed by the for-profit hospital chains. These hospitals charged whatever they wanted for whatever procedures or tests and, they also realized, no one was stopping them. Since then, the healthcare and pharmaceutical industries, and insurance companies began their race to the top, to have a monopoly in the market. At this point, healthcare had nothing to do with human health. It was all about making profit.

Sadly, this is still true today. In his talk, Dr. Jonathan Burroughs, an MD and a healthcare legal expert, testifies that procedures, tests, and prescriptions are ordered if they are profitable, not necessarily because they are important for treating the patient. He summarizes, “In other countries of the world, people get paid for keeping people healthy, but... [in the United States,] we get paid for sickness, and not for health.”

Now that we have seen the roots of the problem, let’s examine what is preventing our society from rectifying this. What our failing and destructive healthcare system needs is government regulation and centralized negotiation with these different parties playing their tug of war. In many other countries, the government directly negotiates with the healthcare providers, pharmaceutical industries and medical device manufacturers to set an affordable price standard for everyone. But in the U.S., the prices of tests, procedures, and drugs are set by the private providers. Yet, the current political structure does not allow the government to intervene. This is called neoliberalism, of which the basic tenet calls for “freedom from” government intervention.

Figure 3.

Net worth and financial distribution in the U.S. (whorulesamerica.ucsc.edu)

People who can benefit the most from these theories are the elite group and the corporate persons which is a very small portion, less than 1%, of the entire population (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the middle and lower class populations are exploited, or even abandoned. However, it is often hard for us to see how our lives are directly affected by these policies because of the prevalent beliefs that “government is bad” and “markets are good.” A political theorist and professor at UC Berkeley Wendy Brown calls it the “neoliberal demonization” of government. With these ideologies and theories embedded in our society, we let industries lobby to get laws in place, instead of the government leveraging and advocating for the patients. And those laws are there to protect their interest, not the interest of us, people, and the public health. When President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act, a.k.a. Obamacare, lobbyists wrote it so that private institutions are allowed to charge up to 20 percent administrative cost. In 2018, Martin Shkreli, former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, was criticized for increasing the cost of a life-saving drug Daraprim from $13.50 to $750 in the name of research for new and better drugs. This was an over 5,000 percent increase that could severely affect the lives of patients with immunodeficiency and cancer. These examples show how the lives of many could be extorted in the hands of few, and how this is justified in the name of making a profit. In this way, neoliberalism aggravates the problem of wealth inequality, and consequently inequalities and inequities in health.

This point becomes clear when we turn to Adam Gaffney’s public school analogy. Gaffney invites us to imagine a society where public schools are funded in the same way as hospitals are funded. What will happen? Teachers will be billing each student with specific interests differently, depending on the length, complexity, and intensity of the lesson they provided — just like how patients with different diagnoses are billed according to the tests, procedures, and treatment they received. Gaffney explains that schools will “compete” for wealthy students and avoid poor ones. Profitable schools will continue to prosper while the unprofitable schools will fall behind in terms of the quality of education, facilities, and resources, go bankrupt, and/or close down. This will start to create zoning of districts that divides people according to their socioeconomic status. In other words, if you were born in the lower, working class, and have no profits to offer these institutions, you are doomed. We know this is not normal. Then, we must also see that the way hospitals and healthcare industries operate now is not normal.

The current system affects people of low-income class or with preexisting conditions most severely, when they are often the ones in need of care the most. A study by Becker and Newsome reports that people of low socioeconomic status are likely to be in poorer health conditions and have higher levels of dissatisfaction with healthcare than those of the middle-income class. Most of us take this inequality for granted. But, how do we make sense of this? People’s socioeconomic status decides what type of insurance they are going to have. This not only decides the quality of health care they receive but also the amount of time and effort people have to spend to get their treatment approved or to figure out how much is going to be covered. Beker and Newsome’s finding suggests that low-income people spend a much greater time dealing with health care bureaucracy than the middle-income people. This adds more frustrations when people are already going through a physically and mentally stressful time trying to get an appropriate treatment. Furthermore, hospitals and other health care facilities in low-income areas tend to have higher turnover rates of physicians. As we have seen in the public school analogy, these facilities are also more likely to close down, limiting people’s access to care. All these factors make it difficult for low-income people to visit doctors routinely and to form a good relationship with their physicians. What about people with disabilities and preexisting conditions? Sakellariou and Rotarou write, from a neoliberal perspective, they are viewed as “costly bodies who use up limited healthcare resources or as potentially financially burdensome.” To avoid such cost, neoliberal policies call for stricter eligibility criteria, and reduced disability claimants. From a shallow view, it could be very tempting to overlook that Medicaid and Social Security Disability Benefits are there and have solved all the problems. Yet with a deeper awareness, we know that the problem arises from a more fundamental level. It is the policies that prioritize profit over people, or the absence of policies that prioritize people, that is putting people into the vicious cycle of social exclusion/ inequality, unemployment, poverty and illness.

Now that we’ve seen the depth of the problem surrounding the healthcare system in the U.S., you may ask this question again, “What do we do?” This time, I would like to give you an answer that is different from “Don’t get sick,” a more feasible, and hopeful solution. I would like to begin by showing you examples of how some other countries have successfully implemented a healthcare system that promotes public health and common good.

Let’s first explore France, a country often regarded as having the best healthcare system in the world. France has a universal health coverage system and enrollment in statutory health insurance is mandatory, so everyone in the country, regardless of age, income or social status, has insurance. The insurance reimburses about 70-80% of the total charge, but also because the government sets the budget and oversees to keep the price of medical care low, the price of medical services stay reasonable and affordable. In addition, because everyone has health insurance from birth, people are more likely to visit doctors even with minor health issues. This means more preventative treatments are possible, and this saves a lot of money, too. This is unlike the U.S. where a lot of patients only visit doctors in the worst case scenario or end up in the emergency room. Another aspect of France's healthcare system that differs from the U.S. is that French patients freely choose their own doctors, instead of the insurance company dictating which doctors you can go to. There also exist voluntary private insurance companies and private hospitals. In fact, the private for-profit hospitals make up one-fourth of the total hospital capacity and activities. This is approximately the same percentage in the U.S., but how do the two countries have such a different healthcare system? The key difference is that in France, the government directly regulates the policies for public health, and they have the bargaining power.

Australia is another country that gets a good amount of attention when it comes to healthcare. Not surprisingly, Australia also has a universal coverage system, and it operates in a similar manner as in France. The enrollment in public health insurance is automatic for all citizens and residents, and complementary/supplementary private insurance coexists. Australian patients, too, choose their own doctors. Australian physicians can set their own price for the services they provide, however the government still regulates so that a maximum out-of-pocket fee is limited to about USD 60 per service. The government also regulates the price of private health insurance and pharmaceutical drugs and therapeutic goods. The healthcare system in both France and Australia may not be perfect, but these examples give us hints about what a more democratic healthcare system would look like. They show us that having greater regulations at the government level is essential in reforming our healthcare system, and for promoting patient autonomy. They also prove to us that public and private institutions can coexist. With a little less greed and a little more humanity, we can achieve a more efficient, equal and ethical healthcare system.

Now what about us? What can we do, as a potential patient, doctor, and also as a member of a democratic society? We often think that our presence is so small that we cannot make an influence on society. We are also so used to this broken system that we feel hopeless and even indifferent towards the urgency of making an improvement. However, we have Congress people like Pramila Jayapal pushing the Medicare for All bill to increase accessibility and to deliver affordable and appropriate care for everyone in the country. We also have doctors who support this single-payer system so that they can see their patients longer instead of spending more time with computers documenting and doing paperworks for billing. In fact, the U.S. has recently taken a step toward a better healthcare system by legalizing the transparency of hospital costs. We as a community and as a society can work together.

I am not a healthcare expert or a political scientist. I am a college student who has the ambition to become a physician who cares for the uninsured, under-insured, and socioeconomically challenged communities. Pursuing this path has many financial obstacles and conflicting ideals, knowing that our society is accustomed to capitalism fueled by neoliberal ideologies. However, I believe that having the deeper awareness of the systemic problems itself opens up the path for us to make change. With this awareness in our head and heart, and with the right to make a voice, to protest, and to vote, we will be able to make the right choices.