Goodbye Darwin, Hello Darwin

By Mary K / Winter 2021

I: Tina

I began community college in 2017, the same year as my best friend, Tina. We became close in classes and even had the same major. When nearing the completion of our prerequisites to transfer to university, I applied and she didn’t. Despite starting at the same time, we’ve had radically different journeys. And a big reason for that is because Tina has Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Basically, she can’t communicate or have social interactions in the same way a neurotypical can (Autism Society, para. 4). Some characteristics of this disability include repetitive movements, difficulties with changes in routines, and hypersensitivity to sound, light, touch, smell, and taste (para. 5).

Before I knew Tina, I wasn’t aware of the challenges that come with being on the spectrum going through very basic life movements. She showed me several programs she was a part of that provided her aid in schooling. Furthermore, she had several accommodations such as time-and-a-half on her exams, and note takers.

Continuing on, at the end of the semester I asked how her final exam that morning went. I was heartbroken when she told me that she had a sensory-induced migraine, which led to a panic attack. She cried in the bathroom the whole time. By the grace of her professor, she was able to get the final waived. She took the next semester off.

Given that she was afforded several accommodations and opportunities to succeed, I often scratched my head wondering why she wasn’t able to finish school at the same pace as me. As a neurotypical person who got no accommodations, I didn’t understand what else there was to do for her.

II: This Doesn’t Make Sense

Why does this happen though? There is plenty of anti-discrimination legislation that protects these vulnerable populations. The American with Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990) was a substantial step forward for the disabled of America, which covered a wide range of disability-related issues (accessibility, discrimination, quality of life, etc.). The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 1975) mandated that students with disabilities receive free quality education with reasonable accommodations (U.S. Department of Justice). Particularly in the education sector, disabled students receive more support than ever before.

When transferring from education to work, there are several forms of support for disabled individuals. The ADA made many advancements for people with disabilities in the workplace. It requiring employers to provide reasonable accommodations and prevented discrimination in all phases of employment (hiring, firing, promotions, etc.) (U.S. Department of Justice) Even if someone with a disability cannot work, state and federal programs provide aid as well. Social Security and Supplemental Security Income disability programs provide monetary assistance to people with disabilities who cannot work, or can no longer work (Social Security).

So in essence, there seems to be a substantial support system for disabled people in America. If this is so, then why is it that people with disabilities continue to be the most unemployed population in society? One explanation might be that they aren’t trying hard enough. The government has done enough to level the playing field, so the responsibility of failure is now on their shoulders. Looking a little deeper into this issue sheds light on the several factors that contribute to this inequality between disabled and typically-abled people in the effort to “make it” in the world.

III: Patterns of Disability Erasure

The history of the treatment of people with disabilities in the past is often forgotten or is overlooked. The challenges that people with disabilities face are often swept under the rug by means of erasing its presence from the public eye, or in other words, disability erasure. Disability erasure is a method for hiding a disability for the convenience of the typically-abled. This can happen by preventing people with disabilities to exist (via genocide) or by changing how the disability presents. Various historical instances illustrate the evolution of disability erasure.

Erasure of people with disabilities has taken place in several ways. A prominent example of this is the forced sterilization of those who were deemed to have “unfit” or “feeble” minds. Sterilization was forced upon people with developmental disorders (such as autism, down syndrome). This form of eugenics was legally ordained by the supreme court in 1927, and its purpose was to cut out undesirable traits from the population at the source. This supreme court ruling has yet to be overturned (Radiolab).

Erasure can transpire in other ways, too. And perhaps the most effective way to erase the presence of disability in society is to alter how it presents in the world. Deaf people, for example, were the target of erasure by means of enforcing oralism (learning to speak without hearing language) as a means of communication rather than sign language (Harvard University, para. 13). Alexander Graham Bell was a strong proponent of oralism and eugenics (para. 13). In 1872, Bell founded an oralist school that taught lip-reading and learned-speech, despite how sign language had already been shown to be an effective form of communication between Deaf and hearing people (para. 13).

In 1880, the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf was held. Deaf educators debated on whether oralism and sign language should be used to teach Deaf people (para. 13). The congress decided to ban the use of sign language in schools and endorse oralism (para. 13). This is a form of erasure, because oralism was a means to conceal the disability rather than acknowledge it. Oralism was not an effective way for deaf people to communicate. Rather the goal was to ease the burden of communication from the majority, the hearing, and place it on to the minority, the Deaf.

People with neurological disorders were also targeted in efforts to be erased from the public consciousness. The lobotomy was an up-and-coming procedure sensationalized by Dr. Walter Freeman in the 1940’s (‘My Lobotomy’, para. 1). Psychiatric institutions employed this technique by shocking the patient unconscious, then driving an ice pick up their nose into the front part of their brain (para. 8). The procedure (if successful) changed the patient’s demeanor from combative and irritable to calm and agreeable (para. 1). At least that’s what was reported. Freeman failed to describe other effects of the procedure, such as a loss of personality and inability to communicate. If unsuccessful, patients had to relearn basic tasks such as eating or speaking (Charleston). The lobotomy was at the forefront of psychiatric treatment at the time. It showed night-and-day “improvements” to the patient's demeanor and had seemed to significantly improve the quality of life for people with neurological disorders. However, this was a blatant attempt to erase disability by making patients with neurological disorders more agreeable and easier to deal with.

These several instances of disability erasure have evolved into modern forms. Particularly, the structure of medical care is such that it disproportionately affects people with disabilities as opposed to typically-abled people. People with disabilities are likely to have far more hospital visits (38% more) than people without disabilities (NDNRC, para. 2). Because of this, people with disabilities carry the largest burden of hospital costs of nearly 6 times more than non-disabled people (para. 2). This creates an accessibility issue for low-income disabled people. We see its effect knowing that people with disabilities are far less likely to get medical care than those without disabilities (para. 3). Ultimately, less hospital visits for an already vulnerable population leads to lives cut short. We see a similar trend in physical and developmental disabilities alike. People with developmental disabilities live twenty years less than people without developmental disabilities (Dalton, para. 8). Inequities in medical care for people with disabilities make it difficult for them to live a longer and more fulfilling life. This truncated lifespan is another form of disability erasure. By not providing an adequate level of care, people with disabilities are wiped from the earth much quicker than the typically-abled.

Legislation such as the ACA and IDEA were set in place to provide a better standard of education and work-place environment for people with disabilities. Unfortunately, education quality between people with and without disabilities follows this legislation as minimally as possible, especially in poorer areas (Tatter, para. 1). Instead of creating accommodations in mainstream classrooms, it’s often more cost effective to create a separate special education program wherein students with disabilities can receive accessible education. In some ways this is good for students with disabilities. They get to learn at their own pace, and receive specialized instruction that is molded around their disability. On the other hand, this becomes akin to sequestration of people with disabilities away from people without disabilities. Mainstream students will likely never interact with students with disabilities. Because of this, there is a social disconnect between the two groups. Also, the quality of education for students with disabilities is not likely to match that of mainstream education where educators will be “content specialists” in math, english, or science (para. 6). Physical isolation of students with disabilities in educational settings represents modern day disability erasure, as it successfully produces generations of people who are unaware of people with disabilities around them. This is another instance of “out of sight, out of mind” being applied to people with disabilities.

The inequities in primary education spread to higher education and the workplace. People with disabilities are much less likely to attain higher education than people without disabilities (Bureau of Labor Statistics, para. 1). Furthermore, people with disabilities are even less likely to be employed, regardless of level of education (para. 2).

Why does this happen, though? Many of the reasons people with disabilities face inequity in basic facets of our society is due to neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is a policy model that shapes how wealth is distributed in society (Monboit, para. 6). It is characterized by the privatization and deregulation of public services, such as schools, libraries, utilities, etc. and limiting the power of the government. In action, this can take shape in several ways: tax cuts for the rich, endorsing and allowing monopolies in industry, and limiting allocation of resources directed to accommodate vulnerable (but inconvenient in this model of society) populations such as the disabled. Neoliberalist policy disproportionately and adversely affects people with disabilities. Neoliberalist policy causes wealth distribution to primarily feed back into those at the top: the CEOs and the entrepreneurs that we first talked about. The result is the disabled fall farther into poverty. Since corporations drive policy, regulations that protect people with disabilities are peeled back because providing accommodations is a drain on a company’s budget.

IV: Getting Stuck in the Cycle

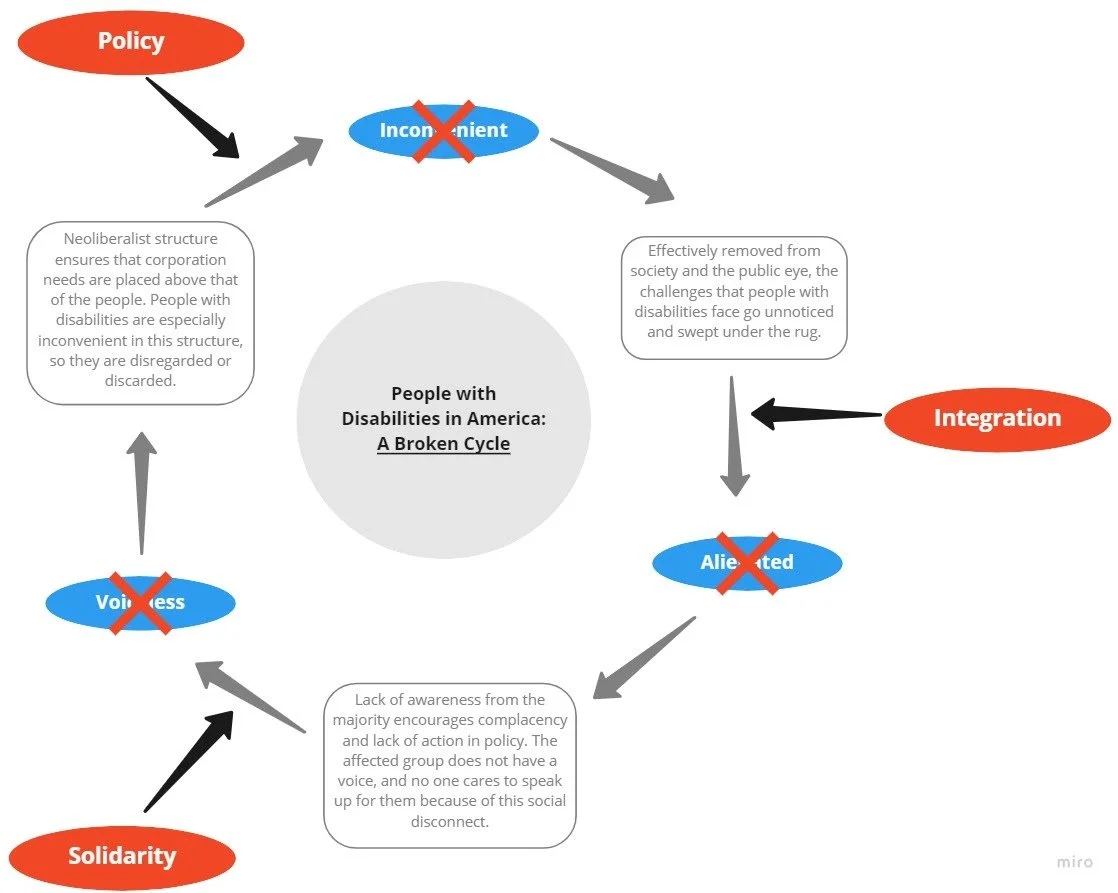

There are three characteristics that shape the cycle of the lives of people with disabilities: inconvenient, alienated, and voiceless (as illustrated in figure 1).

Inconvenience of a particular group of people in society refers to how much they are able to contribute compared to how much they take away. Someone is inconvenient if they take away more than they contribute (e.g. disabled, unemployed, homeless). Our society is structured so that specific types of people can easily access and contribute to it, and this does not include the disabled. When someone is inconvenient, they are perceived to burden the structure.

The first step to combatting this problem is to realize the difference between “impairment” and “disability”, as disability activist Sunaura Taylor describes. Impairment is the physical embodiment of a condition that makes certain activities difficult (walking, seeing, learning, etc.) (Examined Life). This is usually what we believe disability to mean. Rather, disability is the contextual challenges that come with having an impairment in a society, which restrict one’s ability to interact with and participate in society.

An example of having an impairment without disability is Martha’s Vineyard. Starting in 1714, Martha’s Vineyard was an island whose Deaf population climbed to 25% in some areas (Harvard University, para. 1). Because of the large density of Deaf on the island, the inhabitants developed Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (para. 1). Using MVSL, Deaf and hearing people easily communicated with one another. This is special because it showed how society can be structured so that people with impairments are able to participate in their society as equals.

We need to notice how disability is not inability. It is the social structures that inhibit people with impairments. Judging a person with a disability on their contributions to our society is akin to judging a fish on how well they can climb a tree. The effects of being characterized as inconvenient permeate throughout all facets of our society.

The next step in the cycle is alienation, which occurs after neoliberalist policy has limited accessibility to people with disabilities in society. This causes the isolation of people with disabilities to the far reaches of society. It happens by cutting funding from programs that are not likely to be profitable, such as special education. This forced isolation of people with disabilities results in a social disconnect between people with and without disabilities.

As the social gap widens, stigmatization, stereotypes, and dehumanization of disability ensues. It’s difficult to drive policy for people with disabilities when these barriers prevent communication and collaboration between the two groups. People with disabilities become voiceless. Being a minority group, people with disabilities are unable to self-advocate and change policy without the backing of typically-abled people.

V: Breaking the Cycle

This cycle continues to go round-and-round, further stripping protective legislation, further alienating, and further silencing people with disabilities. However, there are ways to intervene in the cycle and create a new one, which is illustrated in figure 2. This is done through solidarity, policy, and integration.

The first step is people like me and you joining in solidarity with people with disabilities. Collaboration between the groups can facilitate people-centered policy that promotes a higher standard of living for people with disabilities. By learning the histories of disabilities in America, we can better understand the policies that harm these groups in order to make changes to policy.

The second step is for the people to ensure the new policies are carried out by institutions that have historically carried out discriminator policy. During this stage, there will be resistance from neoliberalist policy-makers, so reformed legislation will likely be a compromise of what was originally wanted. Therefore, institutions can contribute to this step by avoiding “bare-minimum” effort in executing this policy.

The third step is encouraging integration of people with disabilities into the mainstream world. This will lead to greater understanding and better representation is all facets of life. Integration ensures that accessibility and accommodations are valued as a means of serving its people with disabilities. We can see the benefits of integration. We must shape society around its people, not shape the people around their society. Martha’s Vineyard is a testament to this.

Once integrated, solidarity among the groups will come with ease. Integration is a very important step in this process, because changing laws is not enough: changing the minds of people is how progress is made. By acknowledging people with disabilities as meaningful members of society, we make sure that they are not left behind.

VI: Finding Value in Other Ways

One major flaw that has plagued the progress for people with disabilities is the idea that contributions in society must have a price tag attached to it. We need to understand that the value of people is more than just their monetary output. The vast majority of people with disabilities in America are unable to work at all, so measuring their value in this way has destined them to lose in the game of life we’ve defined. Perhaps this isn’t the answer.

Social Darwinism has been used against people with disabilities to justify their lower class in society. It makes it easier to mistake difficulty with overcoming systemic barriers with personal failure. It promotes the weeding out of undesirable traits from society, namely disabilities. However, something that is often overlooked when supporting Social Darwinism is that Darwin described one ingredient that participated in fine-tuning a species to be the best (Radiolab). That ingredient is variation. By weeding out “undesirable traits”, we also reduce variation in our society. When there is no variation, we become weaker.

There are unrealized rewards to our society by making sure that people with disabilities are able to participate in our society just as much as you or I can. A better understanding of your fellow man. A more varied society. And a sense of togetherness and camaraderie among other members in our society. We can start out small. I join my friend Tina in solidarity by recognizing the faults of the system, and what I can do to end the cycle. Likely, you know someone with a disability as well. Take some time to understand them, and understand them beyond the physicality of their disability. Look into the social structures that keep them in the cycle.

This is a job too big for just me and you. This is going to be the work of the people. We need more people to join in solidarity as well. It’s up to us to educate others around us of these things as well. Perhaps then, we will find solace knowing that our fate is not defined by the forces of nature which Darwin described, but by the humanity and understanding which we welcome into our world.

Figures

Figure 1: Illustration of how systemic discrimination feeds back into itself to further stigmatize and alienate people with disabilities.

Figure 2: Illustration of how systemic discrimination can be intercepted through means of typically-abled people joining together in solidarity to drive people-centered policy and encourage integration.

Works Cited

Autism Society. "What Is Autism?" 26 Mar. 2020. Web. 20 Mar. 2021.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, The Economics Daily, “People with a disability less likely to have completed a bachelor's degree” (visited March 22, 2021).

Charleston, LJ. "An Ice Pick to the Brain: The Horror of the Frontal Lobotomy." 23 Sept. 2020. Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

Dalton, Stevens. "People with Developmental Disabilities Have Much More Life to Live." 10 Feb. 2021. Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

Examined Life. "Examined Life - Judith Butler and Sunaura Taylor." 06 Oct. 2010. Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

Harvard University. "Deaf History Timeline." Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

Monbiot, George. "Neoliberalism – the Ideology at the Root of All Our Problems." 15 Apr. 2016. Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

"'My Lobotomy': Howard DULLY'S JOURNEY." 16 Nov. 2005. Web. 22 Mar. 2021. NDNRC. "CHRIL Article Examines Health Care Coverage and Costs for People with Disabilities." 11 Jan. 2018. Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

Radiolab. "G: Unfit: Radiolab." 17 July 2019. Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

Social Security. "Benefits for People with Disabilities." Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

Tatter, Grace. "Low-Income Students and a Special Education Mismatch." Harvard Graduate School of Education. 21 Feb. 2019. Web. 22 Mar. 2021.

U.S. Department of Justice. "A Guide to Disability Rights Laws." Feb. 2020. Web. 20 Mar. 2021.